Bucephalandra: vegetative metamorphoses

You can believe in miracles or not, but sometimes they do happen. This axiom is consistently confirmed every year by wetland plants of the genus Bucephalandra. Only 5 or 7 years ago, they entered our aquariums, disturbing the steady life of the rest of the aquatic flora. Such traditional plants of the home tank as ferns, Anubias and Cryptocoryne got a serious competitor.

Bucephalandra is a genus of medium-sized rheophytic plants, which are endemic to fast mountain streams of Kalimantan. A huge variety of shapes and colors, as well as the flexibility to the growing conditions, allowed them to sink deep into the hearts of both, hobbyists and ordinary aquarists.

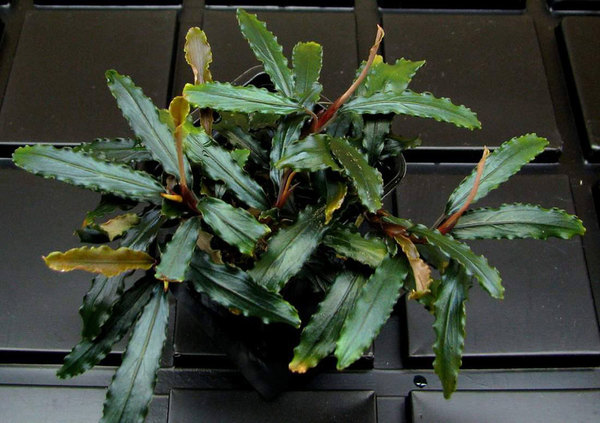

Figure1. Bucephalandra sordidula. Photo: S. Bodyagin.

It is gratifying that Bucephalandra did not stop there and continued expansion, constantly preparing new and new surprises for its admirers. We can attribute to such pleasant discoveries the recent description of 25 new species (the genus has currently 27 valid species), as well as the creation of an intergeneric hybrid between Aridarum caulescens M. Hotta & Bucephalandra bogneri S. Y. Wong & P. C. Boyce. The latter event is significant and unique: it is the first and only example of a successful intergeneric crossing within the family Araceae. In this article, we will continue to surprise our readers (and ourselves) and tell you about a recently discovered unusual type of vegetative propagation inherent in only one species - Bucephalandra sordidula S.Y. Wong & P.C. Boyce.

Initially, we received this plant under the commercial name "Velvet Leaf" and did not notice any special particularities as compared to its wavy-leaved relatives. However, as soon as we forgot about the pot with the emersed plant, having pushed it to the back side of the greenhouse, the plant immediately drew attention to itself again. At first view, we found on the underside of some leaves young plantlets, growing from the central leaf vein (Figs. 1 and 2). It is important to note that the main growth points of the parent plant were healthy with no signs of any disease. What could give an impulse to the development of such unusual buds on the lamina?

Figure 2. B. sordidula: at the first stage of vivaparity process the leaf-bud forms its own root system. Photo: S. Bodyagin.

The answer to this question is crucial because reproduction by leaves is not something unique in the plant kingdom. In particular, almost every fancier of indoor plants experienced the regeneration of many begonias and violets from the leaf. As for the Araceae, here such examples are very rare, but still are the case. The most famous example is the monotypic genus Zamioculcas. The only representative of this genus, Zamioculcas zamiifolia (Lodd.) Engl., can be propagated even by a small fragment of its leaf. At the point where the leaf was broken off a new small tuber appears and gives rise to a new plant.

It is worth noting that all of the examples above refer to the so-called wound meristem reproduction. The nature of this method lies in the defense reaction of plant tissues and their upcoming dedifferentiation. A tylosis develops at the point of cutting off and its meristem cells give birth to new plants. In addition, wound meristem is also able to activate the buds on the cut leaf. The leaf cutting can also be used for propagation of some Schismatoglottis, e.g. Schismatoglottis gui P.C. Boyce & S.Y. Wong. At the same time, vivaparity is typical for Schismatoglottis hayi S.Y. Wong & P.C. Boyce and some ferns (leaflets appear at the end of the lamina, Fig. 3).

Figure 3. Schismatoglottis hayi is an illustrative example of high efficiency of vivaparity as a type of vegetative reproduction. Photo: P. Boyce.

We thus found out that B. sordidula tends to vivaparity, as we didn’t note any mechanical damage of the leaves we observed. We think the trigger of this phenomenon is the high humidity. Despite the fact that from the very beginning the plantlets form their own root system, they develop very slowly. You can force their growth separating them from the leaf and placing them on a wet substrate (Fig. 4).

Figure 4. A hybrid B. sordidula × B. spathulifolia: the cut off leaves (on the left) and the plantlets grown on them after 6 months (on the right). Photo: S. Bodyagin.

After rootage the growth of the plantlets accelerates. After 6 months, they reach adult size. Interestingly, the position of the cut leaf on the substrate doesn’t play any role, a more important condition is to maintain high humidity.

Certain species of Schismatoglottis, S. bulbifera H. Okada, Tsukaya & Y. Mori and S. mira S.Y. Wong, P.C. Boyce & S.L. Low, have a similar type of vivaparity (Fig. 5). However, within the genus Bucephalandra only one species, namely B. sordidula, shows this unusual phenomenon. The ability of reproduction by plantlets can be transmitted. In particular, the interspecific hybrids with B. sordidula as a parent also tend to vivaparity (Figs. 6–8).

Figure 5. Schismatoglottis bulbifera has the same type of vegetative reproduction with B. sordidula. A leaf-bud on the ventral vein of the leaf in the beginning of its development. Photo: P. Boyce.

Figure 6. Like the mother plant, a hybrid B. sordidula × B. spathulifolia produces under overcrowding and high humidity on the central vein of the leaf new plantlets. Photo: S. Bodyagin.

Figure 7. The leaf-buds on the leaf’s central vein of the hybrid B. sordidula × B. spathulifolia. It is important to mention that the leaf doesn’t change its shape after the buds have been appeared on it. Photo: S. Bodyagin.

Figure 8. A hybrid B. sp. × B. sordidula. B. sordidula is here the father plant. The plant can also form plantlets, but while growing they misshape the leaf. Photo: S. Bodyagin.

Well, it's time to finish our little story. Perhaps some readers may think that we have left a lot of loose ends, but there is no reason to worry. Bucephalandra species haven’t said their last word and we are looking forward to reading more and yet more amazing stories about these amazing plants.

The authors thank Dr. Peter Boyce, Dr. Josef Bogner and Dr. Alexey Kirillov for helpful discussions and advice during this article writing as well as Alexander Grigorov for assistance in the preparation of the manuscript.

Literature:

- Bodyagin, S, & Loginov, D. Nachodki selektsionerov, Aquaflora, 2/2013, pp. 32–38.

- Wong S. Y. & Boyce P. C. Studies on Schismatoglottideae (Araceae) of Borneo XXX – New species and combinations for Bucephalandra. Willdenowia, 44/2014, pp. 149–199.

- Wong S. Y. & Boyce P. C. Studies on Schismatoglottideae (Araceae) of Borneo XXXXI: Additional new species of Bucephalandra. Willdenowia, 44/2014, pp. 415–421.

Bodyagin, S, & Loginov, D. Bucephalandra: vegetative metamorphoses. Newslett. Int. Aroid Soc., 37(1)/2015, pp. 21–22.